PROJECT: WILD: A Safari Experience is a fully immersive virtual safari and the first experience built for the Illuminarium.

POSITION: Head of Story

Duties included:

- Concept development. Tasked with the question: What would a virtual safari be? Wrote an initial screenplay and created a visual deck before production to show what WILD could be including the imagery, interactive, physical and sound elements to best utilize an Illuminarium space with all of its technology.

- Went through the footage from the South Africa shoot to see what we could do better and how we could film the content more effectively.

- Figured out the best way to utilize the crew we had for the next shoot. Shot listed all four units including the camera array, the single camera, the jaunt and the time-lapse for the Kenya and Tanzania portions. Spent a month over there location scouting, shot listing and then directing the single camera unit used in the immersive chapters.

- Creatively in charge of the offline / VFX edit – the initial version of the visual and emotional experience.

- Wrote a second script based on this first edit to align all of the disparate departments creatively. Added detailed sound design notes to each scene to give the sound work a dramatic place to start for the Holoplot spatial sound system.

- Scripted the content needed for the green screen work and built animatics with the VFX editor illustrating the action desired. Oversaw the shoot remotely with the supervising producer, the VFX supervisor and the production team in South Africa.

- Created a visual deck for artistic transitions between scenes.

- Built a creative deck for the interactive department.

- Scripted the voice over for the host and the live safari guide.

- Directed the safari guide voice over talent.

PRODUCTION COMPANY: Radical Media, ARCHITECTURE AND PHYSICAL DESIGN: Rockwell Group

The first Illuminarium in Atlanta:

PROCESS:

Step number one is always my favorite step. It’s where I get to imagine what this experience could really be assuming everything in my imagination is possible — the beauty of being a writer. I’m also a research junkie and before this project, I had never been on safari or stepped foot on the African continent. My process started by reading books like The Cry of the Kalahari and memoirs by safari guides. I incorporated this research into a script and then a visual deck to present at our first Illuminarium Lab tests in Brooklyn.

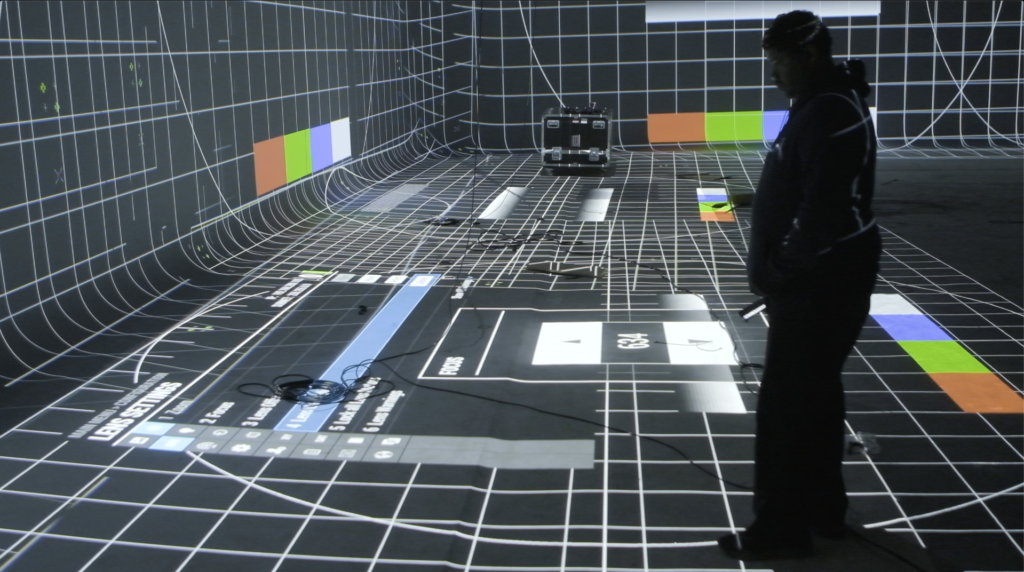

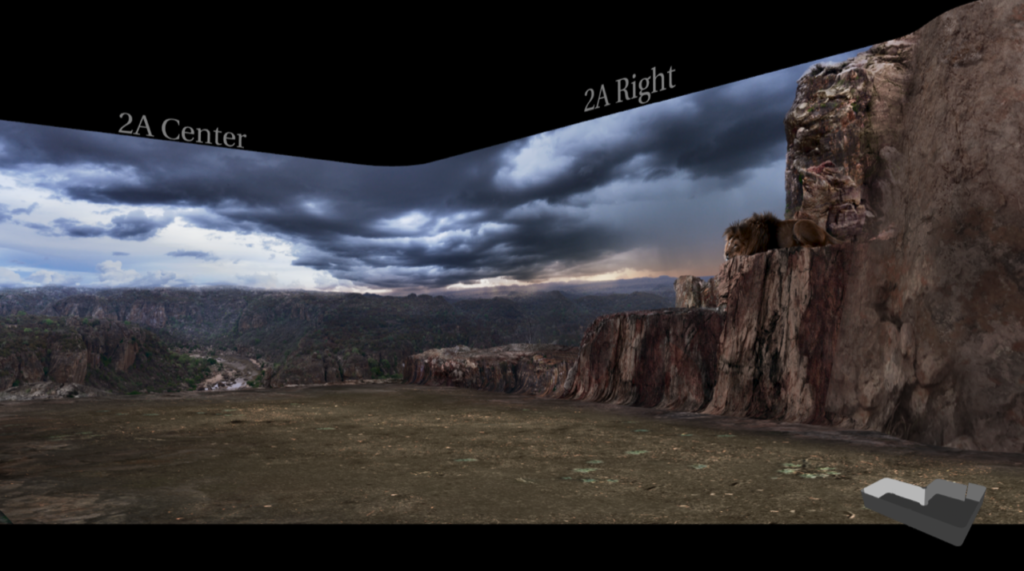

The tests in Brooklyn were a great place to present the scripted experience because all of the partners from all three companies would be there: Alan Greenberg, CEO of Illuminarium, David Rockwell, CEO of Rockwell Group and Jon Kamen, CEO of Radical Media. But the real reason for the tests was figuring out experientially how we could make projections on twenty-two foot walls feel like we are really in the wild… Where should the horizon line be? How do different types of content work in this format? How good do the projectors look with their overlapping streams?

The most important aspect of the Brooklyn WILD lab was testing the camera array. The initial array was composed of three cameras. The tests were needed to see the best set up and overlap to create the most seamless stitch — toed-in vs. toed-out, nodal spacing and tilt.

The tests were extremely helpful on all fronts and the first draft of the story united the three different companies on what a virtual safari could really be. Brian Allen, VP of Creative Technology and Content for Illuminarium, Kelly Vigil, creative technologist from Radical Media and the entire Rockwell Lab needed WILD Lab to test the technology at a real scale.

Clair Popkin, Director of Photography, gained insight from the tests for the first shoot in South Africa. Chris Rouchard, the supervising producer, led the team headed to SA about a week later. I stayed in New York and continued my research on everything from wildlife documentaries and behind-the-scenes of these productions, large scale projection and immersive experiences, theme park techniques and even saw Harry Potter & the Cursed Child on Broadway to take a look at the latest theatrical possibilities. The Illuminarium to me was a place where we could utilize expertise from all of the mediums.

South Africa was a disaster of a shoot. The weather was not in our favor. The country had been in drought for months. The torrential rains were unleashed the moment the crew arrived, destroying days of shooting and making some locations impossible to reach. When the water subsided, there were no animals in sight. The crew returned with empty array plates like the fever tree forest above — elephants added into this design frame I created with Huy Dang, a lovely designer we hired.

Chris Rouchard, the supervising producer, tasked me with creating design frames out of the empty plates to show what these scenes could be with animals. He also thought ahead and threw together an impromptu green screen shoot in SA before they left. With the limited planning time, the first green screen shoot wasn’t ideal, but it gave us some options.

I had done a lot of research on the best wildlife filmmakers in the world while the team was gone. They spent years out in nature to get those amazing shots. We were budgeted for far less time. The project was also given enough money to capture the animals with the array cameras. After my research, I feared this might not be possible and immediately started pondering back up plans.

There was no budget for an editor to work with me until after all of the project was filmed, but I pushed to have at least a tech savvy assistant editor to help me. With an immersive experience, I knew traditional film editing had no place. Editing in this world would involve rotoscoping. I wanted to learn what worked and what didn’t by attempting to edit animals into the existing empty plates.

Boaz Livny, the talented VFX supervisor, taught me loads about rotoscoping. Since we didn’t have motion capture, a moving camera would be a nightmare to rotoscope. He showed me the type of animal visuals that might work and what would not. Chris Rouchard as part of a smart backup plan had been sourcing as much archival animal footage as he could find.

This gave me some options to play with to see how to build drama into these scenes. I even sourced reference footage for Boaz to create a storm over Lanner Gorge — a beautiful dramatic landscape they had captured in SA. The storm could also push the Holoplot sound system to the fullest and utilize the haptic floors.

I realized that the next shoot had to be different. A three camera Sony A7 array wasn’t enough pixels for me to utilize for skies so I had Andrew Gisch, our array specialist whose experience came from VR and 360 video, build a rig out of Sony A7’s so that we could get 360 degrees of time-lapse photography of the skies. Kelly Vigil and I agreed after talking over pixel numbers with Boaz that bringing two Jaunt cameras would be worthwhile — Andrew also owned two of them. Theoretically they might have a high enough pixel count for the room. These could be used remotely so the animals might get closer to the lenses. We would have to also test later to see if these cameras held up in the space.

I also realized that the single camera unit was actually the most important unit we had. Boaz showed me that stitching moving animals in the foreground of the array shots was nearly impossible. Therefore I realized to have animals as close to the guests as we wanted them to be, they would need to be filmed on single camera.

I also saw in working on the design frames that a four or five camera array — we decided to up the number cameras to five Sony Venices for the Kenya and Tanzania portions — would never be as beautiful as a single camera shot. There’s almost no place on earth with a perfect 220 degree view. So single camera would not only need to film animals, but it would also need to capture interesting trees to put into the final array scenes — essentially it would also have to serve as production design.

KENYA AND TANZANIA

Chris Rouchard, Nan Sandle, the line producer, and I flew to Kenya and Tanzania two weeks before the crew to scout three locations in Kenya and five in Tanzania. We brought a 360 camera to capture the potential array locations and I photographed stills of all the interesting animals, trees and ground plates. I then used all of the above to build shot lists for each location, specifying the shots desired from each of the multiple camera units.

Clair Popkin was the main cinematographer with the array camera rig, now composed of five cameras plus a sixth he could operate for additional single camera footage.

(BTS Photography of camera crew by Bram van Woudenberg)

Andrew Gisch and Bram van Woudenberg would operate the 360 time-lapse rig for the sky when they weren’t serving as array specialist and all round grip.

Kelly Vigil was in charge of the Jaunt camera. And Willem Van Heerden, a talented nature cinematographer from South Africa would operate the single camera unit.

I had created all of the shot list decks to let everyone know what they were looking to shoot. It also gave the safari guide scouts the animals to find for us. I spent the first half day of shooting with the array crew and realized there was no point in staying with them. Their field of view was 220 degrees, Clair knew how to shoot beautiful landscapes — he did shoot Free Solo, they had my shot list deck and they had Chris Rouchard to watch over them. The camera unit I realized needed my help most was single camera with Willem.

Willem taught me so much about filming in the wild. He had done it for his entire career. He knew how to quietly get close to the animals. Settle in so the animals adjusted to our presence. He even had animal call & bird calls apps on his phone!

Then I had to unteach him half of what he knew instinctually. In order to rotoscope these shots, we could never move the camera. The frame was not what was important — only the animal inside the frame. We needed to shoot against blue sky or animals with a tree that could also be rotoscoped out with the animals. This style of shooting went against everything a strong documentary camera operator would ever do, but it worked. With our tiny crew and a single safari vehicle we were able to get closer to the animals than the multi-vehicle array unit. These single camera animals became many of the animals in the foreground of the final experience.

The ideal location for the first room was in Solio, Kenya. It was also the only animal reserve with white and black rhinoceros. Chris Rouchard knew it wasn’t worth sending the full crew so he sent me with a tiny break away unit to film it including Andrew and Bram — we were going to shoot it with the 360 time-lapse rig Andrew had built, Willem to capture single camera rhinos and Patricia Wheeler as our unit producer.

The Solio shoot was the last one we would have before returning to the states. Because of COVID the whole crew was re-called without filming the Tanzania locations.

Our full production crew in Masai Mara, Kenya.

POST PRODUCTION

Kevin Matuszewski was an incredible collaborator as a VFX editor. Our entire post team worked long hours to find a way for us to continue working remotely during our Covid lockdown and it paid off. Kevin was my first check point about whether or not single camera shots would rotoscope easily. Claire Dorwart, our tireless post producer then checked for the final say with Melissa Graff — our lead compositor and also a VFX supervisor and colorist on WILD.

We built the emotional narrative experience this way. It was hard without the Tanzania portion we had hoped to film. We were working with only half of the material that we expected to have. Alan Greenberg asked for ways to make it more dramatic. Our solution was a thoroughly planned green screen shoot.

First I spoke with the animal rescuer / trainer who worked with the animals to confirm what each animal he had was capable of doing on camera. I already knew form my research what was natural behavior, but I also needed to be able to capture it on camera.

Kevin and I created animatics for all of the green screen animal action. I scripted scenes to help illustrate each action in detail and then oversaw the green screen shoot remotely with Chris Rouchard, Boaz Livny and the South African crew on location filming the animals. This added much needed action to the experience.

To align all of the departments for both the green screen shoot and afterwards, I wrote a second script of all of the action in the scenes we had edited. I added in the green screen animals and sound design notes to give the dramatic base to the Holoplot sound design. I also built creative decks for visual transitions and the creative and user experience for the interactivity on the floors.

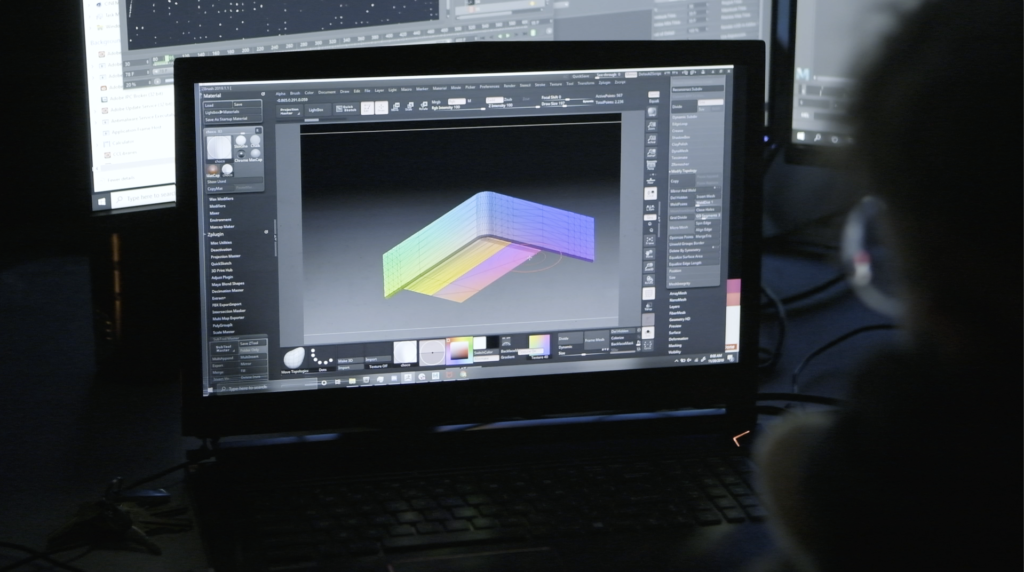

The process from here took a lot of post work. We reviewed the editorial elements and the stitching first through a virtual 3D model and then through a physical model with small scale projectors.

After I finished my creative narrative and experience design work for the first full version of the experience — think of it as the first cut of a film — my main role had completed. Tom Westerlin, a good friend and collaborator I had recommended for the interactive elements, worked with Kelly Vigil and the Rockwell Lab team on the interactivity. Peter Lehman, the most experienced Holo-Plot sound designer around, completed all of the intense sound work. Chris Rouchard supervised everything through til the end incorporating notes from Jon Kamen, David Rockwell and Alan Greenberg. And Boaz Livny, Melissa Graff, Claire Dorwart and Jeff Wolfe oversaw the extreme amount of VFX post work it would take to finish the experience.

Jon Kamen added an additional element to WILD with two gallery chapters — a way to see the animals up close and personal more like traditional film, but projected onto the twenty-two foot walls. A few brilliant British nature DPs went to Tanzania to film these additional chapters.

Chris Rouchard had me return to write the copy for the safari guide monologue and direct both the voice over recording and talk to the first safari guides they were hiring. He also brought me to Atlanta where I could see the final pieces come together on what we had worked on for so long.

WILD was an incredible project to be a part of and something I never imagined anyone would ask me to do.